MOSCONI SHOCKER!

Ruysink out, Jones in as Team USA captain; Lely replaces Chamat for Europe.

In a stunning move, Dutchman Johan Ruysink, the winningest captain in Mosconi Cup history and the architect of Team USA’s resurgence, was not invited back to lead the Americans for a fourth year. Instead, event producer Matchroom Multi Sport announced that Texan Jeremy Jones, a highly respected American player and Ruysink’s vice-captain for the past two years, will take the helm when Team USA travels to London in December to defend the Mosconi Cup title it has won in both of the past two years.

Matchroom also announced that another Dutch coach, Alex Lely, will replace embattled skipper Marcus Chamat of Sweden as the Team Europe captain. Chamat had won three consecutive Cups with Team Europe from 2015-2017 but was at the helm as the Europeans’ eight-year winning streak came to an end in London in 2018 and when the U.S. successfully defended that title in Las Vegas in December.

“The Mosconi Cup is undoubtedly the biggest event in pool,” noted Multi Sport COO Emily Frazer. “It is growing by the second and we continue to push boundaries. The captaincy picks are critical to the event and take serious consideration.

“Marcus has been a fantastic captain,” Frazer added. “He is highly respected and a valued mentor for the pool industry. However, times are changing, and the sport is developing. The decision is no disrespect for Marcus. It was simply time to bring in someone different. The back-to-back losses made the decision a little easier.

“We have had an overwhelming number of applications for the European position, but Alex stood out from the rest. He’s very knowledgeable, with lots of new ideas.”

“Every year there are two possibilities,” Chamat said. “Winning or losing. Obviously, it stings to lose. The Mosconi Cup is tough pressure and not all players are made for that. We had some teams that were so strong, and no one really struggled, like in 2016. But I learned something every year, and every year had good memories. The team spirit was always great, and we had a lot of fun.”

While Chamat’s ouster was mostly expected, Ruysink’s departure comes as a surprise. After leading Team Europe to a 6-0-1 record earlier in the decade, Matchroom appointed Ruysink Team USA captain in 2017 with the charge of revitalizing the down-in-the-dumps American side and helping save the then one-sided event from becoming irrelevant. After a disappointing effort from Team USA in 2017, Ruysink petitioned to have Jones join him in preparing the team for the 2018 Mosconi Cup. Jones, a cerebral player and teacher, was integral as a conduit between Ruysink and the U.S. players.

Following Team USA’s successful defense in December, Ruysink commented that his original plan was for three years, but that, at the urging of his top player, Shane Van Boening, he wished to stay on another year. Matchroom had other plans.

“Johan has played a significant part in the rebirth of Team USA,” said Frazer. “He had a three-year plan and he executed it two of the three, and he should be congratulated. He is unarguably the greatest coach in this game. We at Matchroom will forever be grateful for his services.

“But Jeremy also played a key role in this resurrection. He communicates very well with the players. He is a great player and is in all likelihood the most respected man in pool. The show is progressing, and the captaincy involves 10 times more work and planning than what the public may perceive. The demands, expectations and organization required has been lacking in the structure of Team USA since the beginning. New plans and qualifying structures are in place for 2020, which Jeremy has been heavily involved in. He is ready to keep the fire lit and catapult the team to a new level. He will make a great captain.”

“I’m disappointed about not having a chance to have a real Mosconi Cup goodbye,” Ruysink confessed. “After a difficult start as a European captain for Team USA, I felt I was becoming much more accepted by both the players and the fans. I also felt that the players wanted me to do one more. “But the Mosconi Cup opened the door for bringing my system and methods of fueling players’ passion for pool and knowledge about the game to the United States, so I am very grateful to Matchroom and Emily for giving me that opportunity.

“In the end,” he added, “the Mosconi Cup is a settled phenomenon, and it is here to stay. No player or coach or sponsor is bigger than the Mosconi Cup. I am just very glad that I have been able to do my part in helping it become what it is today.”

For Team USA, Jones’ promotion will allow for the selection and development of the team to be purely American, which was a point of contention to many U.S. fans when Ruysink was first appointed. And having had Jones at their sides for the past two years should make for a smooth transition.

“Jeremy is a good fit for this team,” said Van Boening. “Definitely.”

“Johan did a great job,” said two-time Mosconi MVP Skyler Woodward. “He really helped our guys and knew how to get us ready for something like the Mosconi Cup. There’s so much pressure but he always knew exactly what to do in every situation.

“Personally, I think Jeremy deserves this shot,” Woodward continued. “He’s a great guy and knows the game and knows us players very well.”

“I’m excited, of course,” said Jones. “I always thought I could help the team. I got that opportunity in the last two years helping Johan. I thought it would be a one-year thing, just helping him connect with the players. But the job evolved, and I thought maybe the chance to be captain might come when it was time for the torch to be passed.”

And is taking over for Ruysink bittersweet?

“He said he had a three-year plan, and I think Matchroom just leaned toward me,” Jones said. “I’ve thought a lot about the things I learned from him relative to preparing for the Mosconi Cup and working with the players throughout the year.

“I think there’s a good bond and a lot of trust with the nucleus of the team,” Jones added. “And I think some of it was the American side would like to have an American captain.”

Of course, Jones is aware of the pressure on him to continue the team’s hot streak. Will a U.S. loss have fans or players second-guessing the decision to move on from Ruysink?

“There’s pressure there, but that’s what you want,” Jones said. “I can’t look at it as being in a no-win situation. I feel good about it. Everyone knows the Mosconi Cup is unpredictable.”

To replace himself as vice-captain, Jones said he went “with my gut” and selected journeyman pro Joey Gray of Oklahoma City.

“He’s a great player and he has started to dedicate himself to teaching in the last few years,” Jones said. “I’ve known him since he was pretty young. He’ll mix well with the type of players that will play in Mosconi Cup for America. I just think he’s a good fit.”

The change at the helm of Team Europe sees the return of Lely, a former Ruysink pupil that captained the Euros in both 2008 and 2009. His European squad hammered Team USA in 2008, scoring an 11-5 win in Malta, but lost in Las Vegas in 2009, 11-7.

According to Lely, he is a different coach and leader than he was a decade ago.

“I had very little coaching experience back then,” said Lely, widely praised for his television commentary in recent years. “I’m much more experienced now, working with elite players as well as serving as head coach for the Dutch team for four years. Communication is so important for when the ride gets rough, and I didn’t do a good job of that in 2009. You have to have a structure and core in place to be able to withstand the rough times. You need to be able to fall back on things that have been expressed and determined beforehand.

“The European players that go to Ally Pally in December know how to play,” Lely continued. “We need to have them operate with 100 percent trust and commitment in and towards each other. It’s all about trust, leadership and task.”

“This is a heartbreaker for Marcus,” said fellow Hollander and 14-time Team Europe team member Niels Feijen. “But he had a great run. Taking over from Johan was a lot of pressure and he won three in a row. After five years it might be okay to switch it up.

“Alex has developed a lot since his captain years in 2008 and 2009,” Feijen added. “He worked as a Dutch national coach and did various courses that helped him go beyond just a good trainer and become a good coach. I feel he has a great bag of tools now to bring out the great quality of all of the players. It should be exciting!”

Team Europe will also have a vice-captain in 2020, four-time Mosconi Cup champion Karl Boyes. The former world champion and now TV commentator for Matchroom events will take his opinions from the studio to tableside.

“Having a vice-captain enables you to put your points across and come to a common ground,” noted Boyes. “We both have knowledge about the game and the players, but it’s easy to miss something when you’re on your own. “Alex has a lot of experience playing and managing,” Boyes added. “So, I’m sure I’ll learn a lot.”

“There is excitement in the air following these announcements from players and fans,” said Frazer. “That is always our goal.”

For the Record

John Schmidt’s majestic 626-ball run was the culmination of years of single-minded effort and required a dedicated support team and incredible mental fortitude.

Story By Mike Panozzo

For John Schmidt, it was always personal.

At least, it became personal that day 25 years ago when fellow pro Bobby Hunter introduced him to straight pool.

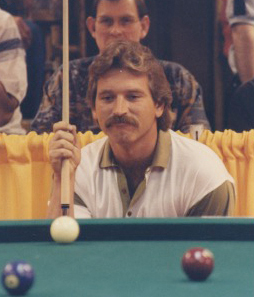

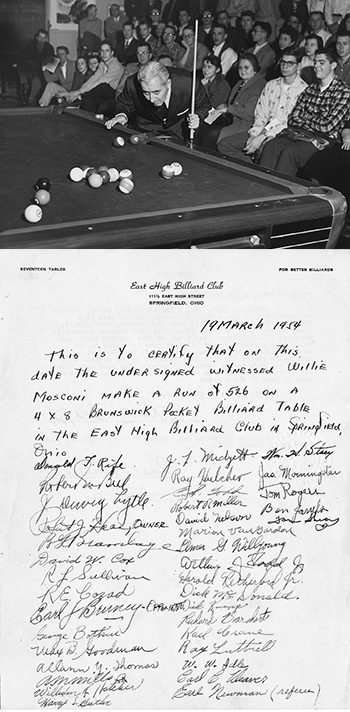

“We were in a poolroom and he was showing me how to play straight pool,” recalled Schmidt. “The first thing I asked was, “What’s the all-time high run?” I’ll never forget it. About nine people in the room all chimed in at the same time, “Willie Mosconi, 526 balls, Springfield, Ohio, 1954.” I knew right then that this was THE record in pool. This was the number EVERYBODY knew.

“Then I looked at all the photos of Mosconi. He was always dressed so dapper. You could tell he was a man respected and revered. I started wondering, “Am I good enough to even get close to a number like that?””

The answer, of course, was yes. On Memorial Day 2019 in Monterey, Calif., Schmidt not only got close, he actually realized the feeling of staring down that very number.

“Once I topped 500,” Schmidt recalled, “and got to the break ball at 504, the panic, nerves, fear, etc., all set in. I don’t know how I didn’t dog it.”

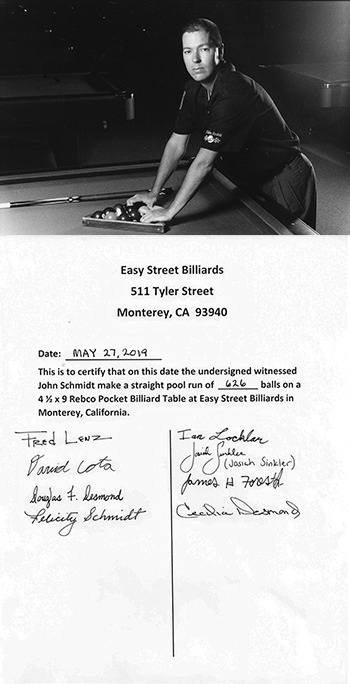

And when ball number 527, the 11 ball, was all that stood between himself and pool immortality, Schmidt found himself overwhelmed by the moment. He paused, put down his cue and excused himself to the men’s room at Easy Street Billiards, the room he all but lived in for 54 days during three extended visits over a 14-month period.

“A bit of a crowd had built up and I was starting to get a little teary-eyed,” Schmidt admitted. “I wasn’t worried about gushing into tears, but I was watering up a bit. I needed to just be by myself for a minute. I splashed some water on my face and gathered myself.”

After taking a deep breath, Schmidt marched back to the table, looking anything but Mosconi-esque in a golf shirt, blue shorts (“I wore them every day because they’re so comfortable!”) and Hoka shoes. With his wife Felicity, benefactor and rack caddy Doug Desmond, and California cuemaker Jerry McWorter sitting silently off to the side, Schmidt lined up the shot he had fantasized about over the years. The 11 ball was just six inches from the corner pocket and the cue ball was eight inches behind. The shot was at a slight angle.

“When I first hit it, my heart stopped,” said Schmidt. “I had the whole pocket but I knew I hit it thick. It went in, but it was into the left side of the pocket. I didn’t want to touch a face as it went in.

“I thought to myself, “My god, if I’d missed a hanger at 527 I would have stepped into traffic.””

With the weight of 20-plus years obsessing over Mosconi’s storied mark lifted, Schmidt settled back into a natural groove. He rattled through six more racks before missing on a combination shot. His record-shattering run had reached 626 balls.

“This number meant so much to me,” Schmidt understated. “I feel like I have been chasing this number my whole life. It was a strange thing.”

Not surprisingly, Schmidt wasn’t really sure how to celebrate the feat. There were no balloons over the table waiting to be released if and when he broke the record. There were no television or newspaper reporters waiting to interview him. There was, in fact, a suddenness to the ending. The long journey was over.

“We just kind of cleaned everything up at the room and went back to the apartment,” Schmidt said.

After cleaning up at their shared apartment in Del Monte Forest along the scenic 17-Mile Drive, the Schmidts, along with Desmond and his wife Cecilia, celebrated at Monterey’s famed Whaling Station Steakhouse, perched above Cannery Row and overlooking Monterey Bay. The hero washed down crab and lobster with several glasses of his favorite cabernet sauvignon.

Having had time to digest the personal magnitude of his accomplishment and reflect on the long road he’d endured, Schmidt shared his thoughts.

“A lot of people think I did this for attention or so people can tell me I’m great,” he started. “I could have been on a deserted island and never met a soul, and I still would have kept trying to top 526. I’ve always been curious about whether I could do it. The skill that’s required to run, say, 250, is so immense that it boggled my mind that [Mosconi] could run 37 racks in a row without hooking himself or missing a ball. It became a personal obsession.

“There are some things that you KNOW you can do, and you’d bet your life on it. I didn’t know if I could do this.”

Not that John Schmidt is a struggling amateur. He has been a top American professional player for more than 20 years. He has won the prestigious U.S. Open 9-Ball Championship, numerous national and regional events, one-pocket titles and, of course, straight pool titles. He has played for Team USA in the Mosconi Cup twice.

But the Holy Grail for the 46-year-old from Hesperia, Calif., has never been a tournament title. It has been, at times, an unhealthy obsession with the number 526.

“This has been a journey of curiosity and self-discovery,” Schmidt acknowledged. “Sure, I love straight pool, but it was more than that. Could I challenge myself like this and hold my nerve together? Did I have the shot-making ability and pattern recognition?

Schmidt never needed an opponent to enjoy playing pool, and straight pool offered the perfect challenge of man vs. himself. The steep odds against him ever reaching 526 never deterred him.

“Just to have a shot after that many consecutive break shots is almost impossible,” Schmidt contended. “On top of that, over all those racks you don’t have a skid or a miscue or a treetop or a roll-off. Plus, you need the skill. Finally, you are shooting knowing that 65 years have gone by since that number happened. That adds pressure because Willie wasn’t shooting at a number. He just kept shooting. I had a specific number that I was chasing.

“Believe me, if anyone understood the odds, it was me.”

Through the years, Schmidt often set days aside to take serious runs at 526. His 400-ball run in Milton, Fla., in 2004 earned him the moniker “Mr. 400” and cemented his reputation as a straight pool big shot. He topped 400 again three years later in Virginia, reaching 403. Only a handful of players had reached that rarified air, including Billiard Congress of America Hall of Famers Earl Strickland (408), Allen Hopkins (421), Ray Martin (426) and Dallas West (429). While legend claimed that New York’s Michael Eufemia had run 625 in the 1970s, the closest recognized run to Mosconi was Germany’s Thomas Engert’s 491.

In 2013, a thread about challenging Mosconi’s 526 drew attention, with Schmidt offering to play 6-8 hours a day, five days a week in an effort to top the mark if someone or some company would give him a $50,000 salary. While discussion was lively, there were no takers.

In March 2018, Schmidt decided it was time to take a concerted run at the hallowed number. He packed up his motor home and drove to Monterey, where the owners of Easy Street agreed to give him a dedicated table over a 26-day period. Schmidt arrived at Easy Street 18 mornings during that period, cleaned the table, polished the balls are embarked on his runs. Incredibly, Schmidt posted 23 runs of 200 or more balls and peeled off 300-plus-ball runs on five consecutive days.

“I was amazed,” he remembered. “Then I realized I was still 200 balls away!”

It was during what became known as “John Schmidt 14.1 Challenge I” that Desmond suggested a different arrangement for the next attempt. Desmond, a 71-year-old retired sales manager, had been making the drive from his Saratoga, Calif., home to Monterey each morning (66 miles) to assist Schmidt with polishing, cleaning, racking and charting. Desmond offered to rent a two-bedroom apartment in Monterey in November and December for Challenge II. The team shopped for food, ate together, watched tape, discussed the day’s efforts and formulated strategy for the next day.

The addition of normalcy to Schmidt’s life made a distinct difference, with Schmidt posting two runs north of 400 balls, including a personal high 434.

“Again, I was still 100 balls short,” Schmidt said, exasperated.

In late January 2019, Schmidt traveled to Southern Indiana to play in the annual Derby City Classic. Naturally, he competed in the George Fels Memorial Straight Pool Challenge, in which players post an entry fee and get a dozen chances to post the event’s high run from a break ball position. (Schmidt posted the fourth-highest run, with 216.) During the event, Phoenix poolroom owner Trent King approached Schmidt with an offer to spend four weeks in Arizona and continue his quest at Bull Shooters, with each session streamed live to pool fans around the world.

The Arizona trip proved to be a turning point for Team Schmidt. While Schmidt authored another personal best – 464 – and ran through five more 300-ball runs, it was information away from the table that helped him turn a corner.

“I learned a ton of important things in Phoenix,” Schmidt said.

For starters, Schmidt started to change habits, change playing strategies and even change his attire.

“I bought a pair of Hoka shoes,” he said. “[Fellow pro] Mike Davis told me about them. They made a huge difference. My feet and legs didn’t get nearly as tired. I also started eating differently. I started fasting and drinking these B-12 smoothies from Whole Foods. I started breaking the balls differently. I was improving every day by learning what worked and what didn’t.”

Just three weeks later, the Schmidts and Desmond were back in Monterey for Challenge IV, a previously scheduled one-month stint.

“We’d already had the fourth block scheduled, so this was happening regardless,” said Schmidt. “And, truthfully, this was going to be the last block. Doug had spent a lot of money to help us, and it was costing me a lot of money too.”

On the second of the 16 days Schmidt played in May he ran 421.

“That gave me high hopes,” Schmidt recalled. “Then I had about a 10-day lull of high 200s and low 300s.”

Perhaps the most astonishing factor in Schmidt’s four-block assault on Mosconi’s run was his perseverance and mental fortitude in the face of 200- and 300-ball “lulls.”

While every long run and new personal high were great achievements, they were, at the same time, failures.

“If I was at Derby City and ran 400 I would be the hero,” Schmidt offered. “I’d be carried off on everyone’s shoulders and I’d have eight people trying to take me out to a nice dinner. But in this environment, there is no fanfare when I mess up. I feel like an idiot and I have to start over. It’s the only time in my career where I’ve done things that I would normally think are great and I feel like the biggest loser on the planet.

“I had hundreds of days that just were not fun. People think a lot of pros can do this, but I want to see how they react after they get a skid at 390 or a miscue at 275, day after day. When you’re on a big run everyone is watching. They’re all off their phones and their jaws are hanging open. Then when you screw up everyone just walks away.

“It’s an awful thing when you miss,” he added. “The livestream in Phoenix was good because it forced me to just rack the balls and start over. There were times I just wanted to break my cue and walk out of the building. But I kept going because I thought at any moment I could reach greatness. There were times I ran a 330 and followed with 170 on the very next shot. That’s hard to do when you’re disgusted.”

The mental focus it takes to endure hours of shooting, days on end, also took a physical toll on Schmidt.

“Some days I would walk in and run 100 four times in a row,” said Schmidt. “Now it’s noon and I’m already worn out. I still have a half day left. Or I’d run 360 and it’s after 6 o’clock. I’ve run past dinner, but I keep playing. Then I get a skid. My whole body is messed up.

“In Phoenix there were a number of days where I’d walk in and run 360 on the first or second shot,” he said, laughing at the recollection. “Now my feet hurt, my neck hurts and we’ve just started. It’s streaming live and people are yelling, “Yeah! Let’s put on a show!’ Meanwhile, I’m dying.”

Still, by Challenge IV, Schmidt’s new routine was paying dividends. In the evenings, Felicity would make dinner while John and Desmond logged the days numbers and discussed strategy.

“We constantly tested things,” Schmidt said. “Sleeping more, sleeping less. Eating more, eating less. Breaking hard, breaking soft. Every day, Doug and I were throwing stuff at the wall to see what would stick. Doug is a good player and is very knowledgeable. He’d say, “Why don’t we hit the break softer tomorrow?’ Or, “Let’s use high left on the break ball.'”

Schmidt would watch the evening news and retire early. Schmidt would rise by 6 a.m. and have his morning cup of coffee with Desmond. On the way to Easy Street, they would stop at Whole Foods to grab a few egg croissants and some fruit. Once at the poolroom, they would vacuum the table, polish the balls, close the drapes and start the camera. It became a ritual.

It was late in the day a week into his final trip to Monterey when Schmidt found himself deep into what he thought might be a record run. He cleared 450. Next, he blazed past his previous record of 464. Suddenly, he was knocking on the door of 500.

At 490, Schmidt faced a break shot to the right of the rack. It was a relatively routine break shot for Schmidt.

“I dogged my brains out,” Schmidt said in disgust. “And I will admit that it was 110 percent because of the pressure. It was right in front of me and I thought, “This is it.’ And I completely fainted. I let everyone down…Doug, my dad, my wife, my family, my fans. It was more heat than I could handle.”

Not surprisingly, Schmidt took a day of rest following the 490.

“Listen, I’m 46,” Schmidt confided. “I tried to wrap my head around accepting that failure was more likely than success.”

Twelve days later, on Monday, May 27, Schmidt strolled into Easy Street for another day of attempts. Unofficially, he had eight more days with which to break the record.

He wouldn’t need them.

Schmidt limbered up with 126, then 28.

“It was a perfect start,” he recalled. “I was still fresh. I had good energy. The conditions were perfect.”

So were his patterns. He blazed through rack after rack. When he got to his break ball, Desmond would calmly grab their trusty Sardo Rack and corral the balls for the next rack. A few hours later, Schmidt was well into the 300s. Soon after, he had topped 450 and the pressure began to build.

“470 to 530 I was a nervous wreck,” Schmidt admitted.

Ironically, at 490, Schmidt was faced with the very same break shot he’d botched two weeks earlier. Schmidt glanced over at Desmond, but Desmond refused to make eye contact. Schmidt felt nauseous.

“It was miserable,” he said. “If there was a heart monitor, I could have lit up an entire city.”

This time, however, Schmidt did not “faint.” The 5 ball sailed smoothly into the corner pocket and the cue ball dove into the rack, creating a nice spread of balls.

“Well,” said Desmond, matter-of-factly. “Engert is handled.” Having cleared two significant hurdles, Schmidt knew the record was in sight.

Schmidt broke at 504 and worked his way through the rack. At 518, Schmidt made the break ball, but the cue ball found its way into the middle of the rack. He feared the worst. Would he end up tree-topped or trapped? The balls seemed to move in slow motion. At the last second, the balls opened up and Schmidt saw a lane. He had one shot, a missable ball along the rail. It forced him to elevate his cue.

Suddenly, the panic, fear and nerves all set in. To Schmidt, virtually every shot the rest of the way looked nearly impossible.

“My heart was going a million beats a second,” he insisted.

Having successfully dodged that bullet, Schmidt knew Mosconi’s elusive 526 was in this single rack. A few balls later, Schmidt opened up a small cluster of balls.

“You need four,” Desmond offered.

The balls were right in front of him for the taking. Strange thoughts started to creep into Schmidt’s mind. What if they’d miscounted? What if they moved the coin (used to count racks) wrong and he was really only at 512?

So after Schmidt returned from his bathroom break to pocket 526, there was no celebration. No jumping up and down. No hugging.

“I didn’t want to beat the record by two balls,” Schmidt rationalized. “I wanted to put up a number that might last as long as Willie’s did. I know how hard it is to run this many balls.”

Schmidt continued for another 100 balls, finally missing on a combination at 626. “It was a shot that I could have made, but it was very missable,” Schmidt said. “If the run had to end, that’s the way I wanted it.”

Not surprisingly, news of Schmidt’s run blew up pool’s corner of social media. The New York Times heralded the accomplishment and a local Monterey television station did a short piece with Schmidt. Fans and fellow pros offered their congratulations.

“It is my proudest moment,” acknowledged Schmidt, “and the fanfare and congratulations from my fans and peers was way more than I thought it would be.”

The news, however, also sparked debate over the merits and significance of Schmidt’s 626. Critics claimed Mosconi’s run, completed in an exhibition match, was made during “competition,” while Schmidt simply set up break shots to start his runs.

“The criticism and skepticism have bothered me, to be honest,” Schmidt said of the posts. I can’t believe some of the things people have said. To me, it’s a small-minded mentality. In the end, though, it’s been about one percent of the comments.”

It appears that the Billiard Congress of America, recognized keeper of the sport’s official rules and records, has found no fault with Schmidt’s run. In early June, Desmond flew to the BCA office in Colorado with the unedited videotape. BCA officials Rob Johnson and Shane Tyree watched the entire four-hour plus video, and while no official statement has been released, the BCA is expected to recognize Schmidt’s effort as a “record exhibition high run.” It is also expected that the run will be submitted to the Guinness Book of Records.

In the meanwhile, Schmidt has been huddling with friends and advisors to discuss the best ways to capitalize on the record. An edited (for time) version of the video has been prepared but has yet to be released.

“Honestly, I have no idea what I’m supposed to do with the video,” Schmidt confessed. “I’ve got to monetize this to a degree. I don’t really make money in pool. It is an opportunity for me and I can’t let that pass by. I’m not going to simply release this video for free and end up dying broke behind a Walgreens. If the world won’t allow me to get something from this video, then I guess the world will never see it.”

Schmidt contends that he has not shot an inning of straight pool since Memorial Day. “I really want to put together a nice run the next time I step to the table,” he said. “It’s ego and pride. It’s important to me to run 250 or 300. The inning after that I won’t care.”

How Schmidt’s 626 will be remembered in pool lore remains to be seen. Will it carry the same mystique as Mosconi’s 526? Will it last as long?

Schmidt isn’t sure himself, but he is understandably proud of the effort and the result.

“I feel like this whole journey brought the pool world together a bit,” he said. “It was nice to see everyone talking pool and talking about straight pool again.”

LION ROARS INTO HALL OF FAME

Over the years, Alex Pagulayan, the comical, mischievous and lethal Canadian-by-way-of-the-Philippines pool star, has parlayed his talents into the World 9-Ball Championship, a U.S. Open 9-Ball title and a pair of Derby City Classic Master of the Table crowns. Those achievements have now earned the 41-year-old “Lion” the “ultimate accomplishment,” induction into the Billiard Congress of America Hall of Fame.

The United States Billiard Media Association announced that Pagulayan will enter the sport’s most exclusive club, along with table manufacturer/promoter Greg Sullivan and Johnston City Hustlers Jamboree creators George and Paul Jansco. All will be formally honored during ceremonies at the Norfolk Sheraton Waterside Hotel in Norfolk, Va., on Friday, Nov. 1.

Pagulayan, who earned election in a run-off against England’s Kelly Fisher after the two had tied on the initial ballot, will enter the Greatest Players wing of the Hall of Fame. Sullivan, 70, and the late Jansco brothers will be honored in the Meritorious Service category.

“I don’t know what to say,” said Pagulayan after being informed of his election. “For a pool player, this is the ultimate accomplishment, right? And I’m happy to become the first Canadian in the BCA Hall of Fame.” Pagulayan, who moved from the Philippines to Toronto at 16, made his presence felt in 2002, when he reached the final of the U.S. Open 9-Ball Championships. After losing to Germany’s Ralf Souquet in the title match, Pagulayan, then 24, reached the final of the World Pool Championship a year later. Again, he lost in the final. Again, he lost to a German player, Thorsten Hohmann. But it was clear that Pagulayan had championship ability, and in 2004 he returned to the title match at the World Pool Championship in Taipei, Taiwan. This time he emerged victorious, topping local hopeful Pei Wei Chang for the title. A year later, Pagulayan exorcised his U.S. Open 9-Ball demon as well, winning the title. In addition to World Summit of Pool and World Pool Masters titles, Pagulayan is the only player to have won titles in all three divisions of the annual Derby City Classic — One-Pocket, Banks and 9-Ball. He also earned Master of the Table titles in 2015 and 2016.

“The Derby City All-Around titles are my biggest career highlights,” Pagulayan said. “They are such big fields and you have to play all three games well. And it’s really hard to win all three disciplines. I feel like I won pool’s triathlon.”

It was the first year of eligibility for both Pagulayan and Fisher. Each were named on 62 percent of the ballots, forcing a run-off vote. In the special election, Pagulayan received 21 votes, while Fisher received 16. Holland’s Niels Feijen (27 percent) and American Corey Deuel (24 percent) were the next highest vote-getters on the initial ballot. Shannon Daulton, Jeremy Jones, Stefano Pellinga, Vivian Villarreal and Charlie Williams were named on less than 10 percent of the ballots.

For Sullivan, admission into the BCA Hall of Fame caps a life of service trying to elevate pool from a recreation to a legitimate professional sport. An Indiana native, Sullivan became a poolroom owner and, with input from top players, began constructing pool tables to professional specifications.

Sullivan launched Diamond Billiard Products, with his tables quickly becoming the preferred playfield of the pros. Frustrated by coin-operated tables that forced players to use magnetic or oversized cue balls, Sullivan is also credited with introducing optical sensor to coin-op tables so that standard cue balls could be used. For Sullivan, it marked another victory in putting professional equipment into the hands of all players.

In the 1990s, Sullivan contracted the Pantone Company to research the optimum color for pool cloth. The testing resulted in the Tournament Blue prevalent in today’s professional tournaments.

As a lifelong fan of the Johnston City Hustler’s Jamborees of the 1960s and ’70s, Sullivan launched a similar multi-discipline event, the Derby City Classic, in 1998. The annual event has drawn thousands of professional and regional players to Southern Indiana for 21 years.

“I have to say, I’m in shock,” Sullivan said when informed. “My whole life has been about pool, just trying to turn it from a game to a sport. It’s all I’ve ever done.”

That George and Paulie Jansco should join Sullivan in the same Hall of Fame class is appropriate, since the Southern Illinois club owners founded the famed Johnston City Hustlers Jamboree and All-Around Pool Championship in the 1960s. The Janscos contributed to the pool’s romanticized image as a gunslinger’s activity. Their promotion of the gambling aspect of the sport contributed to its rise in popularity with the public, with their tournaments drawing media coverage from major television networks and national magazines like “Sports Illustrated.” So popular were the Johnston City events that the Jansco’s launched a second event, the Stardust Open in Las Vegas. The Janscos could also be credited with moving 9-ball and one-pocket into the game’s forefront during a time in which straight pool was considered the only professional game. They were also among the first promoters to welcome integrated fields, paving the way for players like African-American Cicero Murphy to compete for world titles. George Jansco passed away in 1969. Paul Jansco died in 1997.

Taking A Mulligan

Matchroom’s acquisition of the U.S. Open 9-Ball Championships was met with great joy by the pool community. Bold plans and grandiose promises heralded a bright future for America’s oldest and most significant major pool tournament. A guaranteed purse of $300,000 for the 2019 event was announced when entries opened to 128 players. The response from players around the globe was so swift, despite the $1,000 entry fee, that the field was opened and quickly grew to 175, then 200 and finally to 256. More than 100 players asked that their names be placed on a waiting list.

Not unreasonably, most players assumed that since the number of entries doubled, the prize fund would also jump. Simple math shows that a $300,000 guaranteed purse with $128,000 in entry fees equals $172,000 in added money. With 256 players, that $172,000 would bring the total prize fund to $428,000. Makes sense. Even if Matchroom only added $100,000, some rationalized, the purse would still be $356,000.

So, imagine the players’ surprise when Matchroom quietly posted the prize list on its website yesterday, indicating that the total prize fund would remain at its originally announced $300,000. Just $44,000 added to the U.S. Open? Heck, Barry Behrman’s U.S. Opens routinely featured $50,000 added. Some players expressed disbelief. A few others were flat out angry. What happened to all of those big promises? This is a Matchroom production, right?

Of course, everything is not quite as simple and clear cut as it seems. “The cost of this event is staggering,” Matchroom Multi Sport COO Emily Frazer said, when asked about the prize fund surprise.

It seems money that might have been added to the prize fund was gobbled up in staging and production costs.

Honestly, I understand both sides of this. The players have every right to be disappointed in the prize fund. And Matchroom has every right to spend its money where it sees fit in the production of an event.

In an effort to get each side to understand the other’s concerns, I offer the following comments:

To Matchroom — A $300,000 event doesn’t impress players if the entry fees account for 85 percent of the purse. Players are travelling from all over the globe, at great expense, because you have a pristine reputation and you’ve gone to great lengths to tout your takeover of the U.S. Open as game-changing. They are coming because it says “Matchroom.” These players are paying a $1,000 entry fee, at least that much to get to Las Vegas, $200 a night for lodging, $6 for a bottle of water and will be prisoners in the arena at Mandalay Bay because the field needs to be trimmed from 256 to 16 in three days. And obviously, going from 128 to 256 players with no increase in prize fund has an adverse effect on the prize distribution. So, don’t blame the players if they feel somewhat disrespected. Staging and production costs are astronomical? I get it. But the players did not demand that the event be at the price-gouging Mandalay Bay, yet they have been punished.

Beyond that, the World Cup of Pool ($250,000) and World Pool Masters ($100,000) are 100 percent added money (invitationals with no entry fee). The U.S. Open’s $44,000 in added money makes it the fourth largest added-money pro tournament of 2019 — the World 10-Ball Championship ($100k), the WPA Player Championships ($50k) and the International 9-Ball Open ($50K). This U.S. Open 9-Ball Championships qualifies as the lowest tier WPA points event. That’s not Matchroom. Matchroom sets the bar, it doesn’t limbo under it.

To the Players and Fans — If anyone in this industry deserves the benefit of the doubt, and the gift of a mulligan, it’s Matchroom. If they can be faulted at all in this matter it is in focusing so hard on taking the event itself to the next level. “We’re going to take this event and make it mainstream,” was Matchroom founder Barry Hearn’s message when he announced the company’s acquisition of the U.S. Open.

That doesn’t mean simply posting a huge prize fund. That means creating a must-see event that has people buzzing. I get that too and creating that perception costs money. Look no further than the Mosconi Cup, pool’s only true must-see event. Matchroom took an event that was already successful and ramped it up another level in 2018. That gamble didn’t come cheap, but it paid off. The result? The players will benefit next year with double the prize money. From the sound of it, staging and production plans for the U.S. Open are every bit as bold.

And that is what players and fans should understand and accept this year. Give Matchroom a prize fund pass in April and let them focus on making the U.S. Open 9-Ball Championships the Mosconi Cup of open tournaments. The impact will be long-lasting and the reward to the players is certain to follow.

Pool’s Olympic Bid Fails

The organizing committee for Paris 2024 released a press kit on its

recommendations to the International Olympic Committee. The committee

recommended break dancing, surfing, skateboarding and sport climbing.

Other sports that were included as “finalists” were baseball, squash and

karate.

In recent Summer Games, the IOC has allowed the host country’s

organizing committee to propose new sports. Baseball and karate will be

included in the Tokyo 2020 Games, along with surfing, sports climbing

and skateboarding.

The Paris 2024 Organizing Committee recommended the four sports to

“emphasize its goal of creating spectacular, urban and sustainable

Games. These will not only provide a fitting showcase for athletic

performance but also engage young people and the wider public through

lifestyle sports.”

The World Confederation of Billiard Sports (WCBS), the world governing

body for all billiard sports and a member of the IOC, launched an effort

to have billiards included in 2024 by forming a Billiards 2024

Committee. The committee hosted a press conference to announce its

intent at the Eiffel Tower in Paris in early December. The WCBS also

launched an online petition to demonstrate the sport’s worldwide appeal.

The World Snooker Federation (snooker), World Pool-Billiard Association

(pool) and World Billiard Union (carom) make up the WCBS.

Billiards 2024 Committee Coordinator Jean-Pierre Guiraud was not

available for comment at the time of this post. More information will be

released as it comes in.

Good Things Come To Those That Wait

That old adages seems perfectly appropriate in 2018, as former champions Gerda Hofstatter-Gregerson and Kim Davenport earned election into the Billiard Congress of America Hall of Fame, the BCA announced today.

The Austrian-born Hofstatter-Gregerson, 47, had been on the Greatest Player ballot for seven years and finished second in voting three times. Davenport, 62, had been on the Greatest Player ballot for nearly 20 years. He was recommended this year by the Veterans Committee, which reviews the records of players who had not gained election on the general ballot prior to turning 60.

“My first reaction is, ‘What am I doing in there with all those great players,’” Hofstatter Gregerson. “Honestly, I never expected to get in. Everyone who has gotten in is so deserving, I was just honored to be on the ballot. But I am excited and humbled and honored to be in such great company.”

“It was a long wait and was a little frustrating at times,” admitted Davenport, who resides in Acworth, Ga. “I thought my record was stronger than some others, but better late than never. A hundred years from now people will see my name next to Mosconi’s, and that’s not a bad thing!”

A longtime star on the Women’s Professional Billiard Association Classic Tour, Hofstatter-Gregerson was 10-time European Champion before moving to the U.S. in 1993 to join the WPBA. She won 10 Classic Tour titles in eight years. She also won the World Pool-Billiard Association World 9-Ball Championship in 1995, the WPBA National Championship in ’97 and the BCA Open 9-Ball Championship in 2000.

Davenport hit his stride on the men’s pro tour in 1998, winning the highly regarded Japan Cup and Eastern States 9-Ball titles. After adding three more titles in 1989, Davenport won the Brunswick Challenge Cup in Sweden, the Sands Regency Open and the B.C. Open in 1990, earning Player of the Year honors from Billiards Digest.

Hofstatter-Gregerson and Davenport will be formally inducted as the 71st and 72nd members of the BCA Hall of Fame on Friday, Oct. 26, at the Norfolk Sheraton Waterside in Norfolk, Va.

Mandalay Bay To Host US Open 9-Ball

The 43rd US Open 9-Ball Championship will take place at Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino, Las Vegas from Sunday, April 21 until Friday, April 26, 2019.

Matchroom Multi Sport acquired full ownership of the US Open 9-Ball Championship in a ground-breaking agreement last month and the tournament will move to Las Vegas for its 43rd staging as part of a long-term goal to take the event into the sporting mainstream. The prize fund will be set at a guaranteed $300,000, the biggest ever for the event.

Matchroom Multi Sport acquired full ownership of the US Open 9-Ball Championship in a ground-breaking agreement last month and the tournament will move to Las Vegas for its 43rd staging as part of a long-term goal to take the event into the sporting mainstream. The prize fund will be set at a guaranteed $300,000, the biggest ever for the event.

Matchroom Sport Chairman Barry Hearn commented, “I am delighted that we will be partnering with Mandalay Bay in delivering this new era for the US Open 9-Ball Championship. This is going to be a must-see event for every pool fan in America and we also hope to bring new fans into the game.

“Mandalay Bay was an exemplary host of the Mosconi Cup last year and we are thrilled that they will again host one of pool’s biggest events, the US Open. We are busy working hard to deliver a brilliant tournament next April and will have more news about the US Open in coming weeks.”

Ticket details for fans and entry details for players will be made available shortly. The format will be double elimination on a multi-table set up down to the last eight on the winners and losers sides. The final stages will feature the last 16 players in straight knockout on a single table in a huge arena. All matches will be races to 11 with the exception of the final.

Players and fans wishing to book accommodation at Mandalay Bay for the US Open will be able to take advantage of exclusive rates once tickets are on sale.

Go Big Or Go Home

Frost, who opened Freezer’s Ice House in Tempe, Ariz., says most poolroom owners are “simply behind the times.”

While poolrooms struggle across the country, two industry veterans open sparkling new rooms in the Southwest U.S., with hopes of changing the public’s perception of the game. Ask anyone in the industry how to fix pool or how to save pool or what to do to re-energize pool, and you better not have a dinner reservation in 15 minutes. That one question can elicit a wide range of answers. All it needs is another “Color of Money”… We gotta get kids playing pool instead of video games… The big companies and leagues need to work together to promote the game… These proposals, individually, are not wrong — but they are far from short-term, practical fixes. One person isn’t going to get junior leagues up and running across the country. A slick advertising campaign isn’t going to create millions of new players. Any comprehensive solution will have to gain traction at a grassroots level. Changing perceptions of the game will require widespread effort, in addition to any a top-down solutions. Two new poolrooms — Scott Frost’s Freezer’s Ice House in Tempe, Arizona, and Mark Griffin’s eponymous Griff’s in Las Vegas — are aiming to support those already bitten by the pool bug, while also attracting those adjacent to players and fans. These sprawling spots — Frost’s is 15,000 square feet; Griffin’s is 8,300 — are hoping to improve pool’s image by attracting players and a casual crowd who may just want a beer, a burger and a place to watch the game.

Taking Another Swing

Mark Griffin has done just about everything you can do in the pool world — he’s been a table mechanic, room operator, player, instructor, league operator and tournament promoter. The 70-year-old Alaskan native made his biggest play in 2004, when he sold his room in Anchorage, Alaska, and purchased the BCA Pool Leagues. Relocating to Las Vegas, he went full bore into promoting amateur participation and promoting the BCAPL’s annual pilgrimage to Sin City for the league’s championships. Griffin, a tireless advocate for the game, was neck-deep in the amateur side of the game, while also promoting professional events alongside the BCAPL National Championships. He has organized events under his CueSports International brand, including the U.S. Bar Table Championships, the U.S. Open 8-Ball and U.S. Open 10-Ball Championships, and other West Coast events like the Jay Swanson 9-Ball Memorial tournament. Griffin was also a longtime partner in Diamond Billiard Products, owning the tablemaker’s first building in Tennessee, though that business relationship has recently ended. Never one to sit idle, Griffin faced his most troubling opponent in 2014 — news that he would require a lung transplant. Undergoing the procedure in January 2015, that year was dedicated to his recovery — though one eye remained on his pool projects. “Finally, by the end of the year, I started feeling better. I had my health back,” Griffin said. “And it was just about then that the opportunity to buy the room came about. I thought, ‘Why not?’ I thought I’d take a swing at it.”

Going Off the Road

Scott Frost has spent plenty of time on the road. The 42-year-old has scrambled across the United States for the better part of 15 years. One of the best one-pocket players in the world, he put together an impressive resume — collecting major titles including the U.S. Open One-Pocket Championship, Derby City Classic One-Pocket division and the Legends of One-Pocket title. Having beat Efren Reyes a few times, Frost found it harder to find an action game to his liking. In 2007, he started working in a Phoenix poolhall. Officially the house pro, he spent years learning the business — he wasn’t just there to hit balls and attract in hardcore players and fans. “That was kind of an internship for me,” Frost said. “I did everything there — building the leagues, promoting the room, being the face of the business.” After that business partnership ended in 2015, Frost was left without a motivating force. Burned out after that much time on the road, he started thinking about longer term ways to support himself — while fulfilling a personal promise to his family. “My mother and father were both in business,” he said. “When I found pool when I was 16, they were not thrilled. But about three years later, when I could possibly make a living, they really got behind me. I always promised I would never be a broke, degenerate pool player. “That’s a touchy situation because a lot of my heroes and idols — a lot of those guys showed me what to do and what not to do. I always had it in the back of my mind: someday I was going to figure out a way to build my dream poolroom and make it a success.” Without a room to call his own, Frost called up an old friend, Jason Chance, from Des Moines, Iowa. Chance, a strong player in his own right, purchased his father’s business in 2000, turning Diamond Oil from a steady, if unspectacular, business into a 14-location company on the up. “He’s done so much for me already,” Frost said. “I called him up with my idea — and he said I should start scouting locations.”

A Destination Spot

Griff’s features 25 Diamond pool tables and lures players from national tournaments with a shuttle service.

Back on his feet by the end of 2015, Griffin began construction on the room early the next year. Formerly Pool Sharks, the building needed a complete rehab. Walls needed to be replaced. Flooring had to be ripped up and redone. This wasn’t a matter of slapping on a fresh coat of paint and hanging a new shingle out front. “Really, I don’t know how it stayed open with the health department,” he said. “Everything we have is brand new, besides the ceiling grid. We had to expand the kitchen, replace the air-conditioning units. The bathrooms — you could take those and drop them in the Bellagio and nobody would notice.” Located in a 55,000-square-foot mall on four acres, Griff’s is roughly two miles west of the north end of the Vegas Strip. It has 25 Diamond tables — 17 7-footers and eight 9-footers — in addition to a Chinese 8-ball table and a three-cushion table. Investing nearly $1 million in the project, Griffin sees his room, which opened Oct. 31, 2016, as a standard bearer for the game. “I just want pool to have the facilities that will let people see the game how it’s supposed to be,” he said “It’s a gentleman’s game — treat it like that. There’s no woofing and screaming from across the room. It’s a comfortable, classy place.” “We have security at the door. Heck, the guy’s 75 years old, but he’s here because he knows everyone. He was the doorman at Pool Sharks for years. We haven’t had those issues because people act accordingly.” With Las Vegas hosting so many amateur league championships, Griff’s will certainly be a destination for a certain set of tourists. Along those lines, the poolroom runs a 15-person shuttle back and forth to the various tournament hotels. But Griffin knows steady business is found in developing local and regional followings. “We are definitely catering to the local players and even Arizona players,” he said. “We have weekly tournaments, TAP leagues, APA leagues and independent leagues [in addition to BCAPL and USAPL].” But ask any poolroom owner and he will tell you pool and alcohol won’t keep the lights on by themselves. Griff’s put that expanded kitchen to work and offers full bar service. Other promotions, like karaoke contests, hope to catch attention of those who don’t tote a cue case. The room is also one of the only venues in Las Vegas to be completely smoke-free. (Considering Griffin’s recent medical history, one can see why it’s targeting the non-smoking demographic.) “I want to be a place people will visit because there’s no smoking,” he said. “That is a big deal — and I have people come up to me all the time to say thanks. We have one regular [customer] who is a heavy smoker, but he loves it because the place is nicer.” Due to some licensing issues, Griff’s doesn’t yet have video gaming, but Griffin expects to offer the machines that are ubiquitous in town to his patrons. “You can’t survive in this town without them,” he said. “The grocery stores have them. But we’ll hopefully take care of that in the next few months.” While gambling might be part of the culture in Las Vegas, Griffin feels like he’s already won. With his health and plenty of energy, he’s back being an advocate for the game — though vacations might be more plentiful moving forward. “I’m lucky to be alive, that’s the way I look at it. I shouldn’t be here,” he said. “I’m going to work hard but I also want to travel and enjoy myself.”

A Desert Hot Spot

Frost didn’t waste time when he got the go-ahead from Chance to scout for possible locations for a room in 2016. He visited more than a dozen potential sites in the Phoenix area, eventually setting his sights on a freestanding building at the corner of a bustling intersection in Tempe, Arizona. Just a few blocks south of the Arizona State University campus, the spot promised plenty of drive-by traffic, along with the interior space to build a multi-faceted room with pool tables, a lounge/nightclub area and a bar and grill. But wanting and having are two different things. “People ask what was the most stressful part of this whole project,” Frost said. “Far and away, it was negotiating the property.” Bidding against a local organic grocer, Frost spent three months in discussions with the owner before his bid was accepted.

“It was a lot. One week we thought we had it — the next, we weren’t sure,” he said. “The owner really bought into our concept and what we wanted to do with the place. Once we got that deal, it felt like we were gathering momentum.” Construction began in December 2016, with major renovations to what had been a retail space. Throughout the building process, Frost was onsite as much as possible, working with contractors to ensure the reality matched his vision. “It seemed like a million years because I was coming in everyday wanting to go, go, go,” he said. “But really, in what was accomplished in that time, it’s amazing now that I can look back on it.” Six months later, in late June, with a total investment north of $2 million, Freezer’s Ice House opened with 35 Diamond tables, 12 dartboards and more than 100 TVs. Appropriately enough, the Ice House has three different rooms. In addition to the poolroom, the Hot Spot Lounge is a sports bar during the day that turns into a nightclub later in the evenings.  The Chill Grill is a third area that offers quieter drinks and dining. Like Griff’s play to attract non-pool players, the Ice House is more than chalk and stale beer. “You have to give people a reason to come,” Frost said. “I wanted a place that could have families come in. The dad can play pool, mom can have a glass of wine in the lounge and the kids can play Ms. Pac-man.” Also, like Griffin did with his room, Frost sees the Ice House as a contradiction to the tired stereotype of a dirty poolroom. “I do not say ‘poolhall,'” he said. “There’s a stigma there and I don’t want to be a part of it. This is an upscale poolroom. My partner and I, we want to change the face of pool. This is something that is needed, and it’s wanted by a lot of people.”

The Chill Grill is a third area that offers quieter drinks and dining. Like Griff’s play to attract non-pool players, the Ice House is more than chalk and stale beer. “You have to give people a reason to come,” Frost said. “I wanted a place that could have families come in. The dad can play pool, mom can have a glass of wine in the lounge and the kids can play Ms. Pac-man.” Also, like Griffin did with his room, Frost sees the Ice House as a contradiction to the tired stereotype of a dirty poolroom. “I do not say ‘poolhall,'” he said. “There’s a stigma there and I don’t want to be a part of it. This is an upscale poolroom. My partner and I, we want to change the face of pool. This is something that is needed, and it’s wanted by a lot of people.”

Doing Things Differently

These two rooms are aberrations in an industry that has seen rooms go out of business across the country. So, begs the question, just what makes these guys the ones to be successful in a tight market? Griffin has a simple answer. “I’ve done this before,” he said. “I had the Anchorage Billiard Palace for 16 years.” (He also owned a handful of rooms in San Diego in that time.) Frost, meanwhile, believes his time on the road, along with the years spent working in a Phoenix room, primed him to do it the right way. “I’ve got so many memories and I’ll never regret it,” he said. “But in my opinion, 90 percent of rooms are behind the times. Everybody’s saying the game is dead. Pool isn’t dead. The poolrooms people play in are.”

These two rooms are aberrations in an industry that has seen rooms go out of business across the country. So, begs the question, just what makes these guys the ones to be successful in a tight market? Griffin has a simple answer. “I’ve done this before,” he said. “I had the Anchorage Billiard Palace for 16 years.” (He also owned a handful of rooms in San Diego in that time.) Frost, meanwhile, believes his time on the road, along with the years spent working in a Phoenix room, primed him to do it the right way. “I’ve got so many memories and I’ll never regret it,” he said. “But in my opinion, 90 percent of rooms are behind the times. Everybody’s saying the game is dead. Pool isn’t dead. The poolrooms people play in are.”